Mar 20, 2015

Math in the Art of Braided Hairstyles

Math in the Art of Braided Hairstyles

Hairstylist Clea White of Peoria, Il., can fashion box braids, French braids, micro braids, cornrows, braids with hair extensions, and braids without. "The parting, that's what makes braiding," she recently told the Peoria Journal Star. Braiding comes naturally to White, but the essence of the parting and sectioning lies in a subject that she loved in school — mathematics.

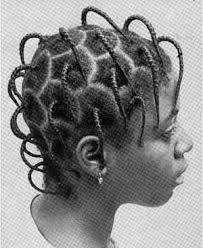

"You can't help but look at these hairstyles and see the geometry," said Gloria Gilmer, a college teacher and educational consultant in Milwaukee. Gilmer has studied and written about mathematical patterns in African American hairstyles.

Gilmer, a founding member of the International Study Group on Ethnomathematics, investigates hairstyles as a way explore how different cultures integrate mathematical concepts into everyday life. "Nobody ever tells you math is natural," Gilmer told the Peoria Journal Star.

Gilmer's work is part of ongoing efforts by some math educators who believe students would be more interested in mathematics if they saw how it applies in daily life. "Schools should have never segregated math from the arts," Gilmer said. "If you miss the integration of math, science, and art, you miss the best part of life."

For White, the perfect part on a customer's head is the foundation for a cornrowed version of the classic French roll, a style that is practical and simple. When she's done, each row curves around her customer's head, evenly spaced and parallel to every other row in a pattern perpendicular to that first, central part. To achieve that effect, White would have subconsciously calculated the width of each cornrow, the length of each strand of hair, and the place where each braid had to end.

Most hairstylists have no idea how much math they are using, Gilmer said. She sees algebra in the formulas they use to figure out how much false hair they need for weaves and hair extensions. She sees physics in the methods they choose to attach hair weaves. But it is the geometry of the braided designs that is the most obvious mathematical concept on display.

Gilmer found that braiders often mimicked shapes and designs found in nature: honeycombs, pineapples, or spirals. And they would repeat the pattern over and over again in the hairstyle, much like quilters repeat patterns in a quilt.

Source: Peoria Journal Star, Sept. 27, 2007.

Click here to visit gallery